Measuring and objectifying observations and phenomena. Numbers. Data. These are the cornerstones of analytics. The presentation and appearance of (apparent) objectivity. Whether in research, health care policy, economics, business, or clinical practice, data is important.

The data doesn’t lie.

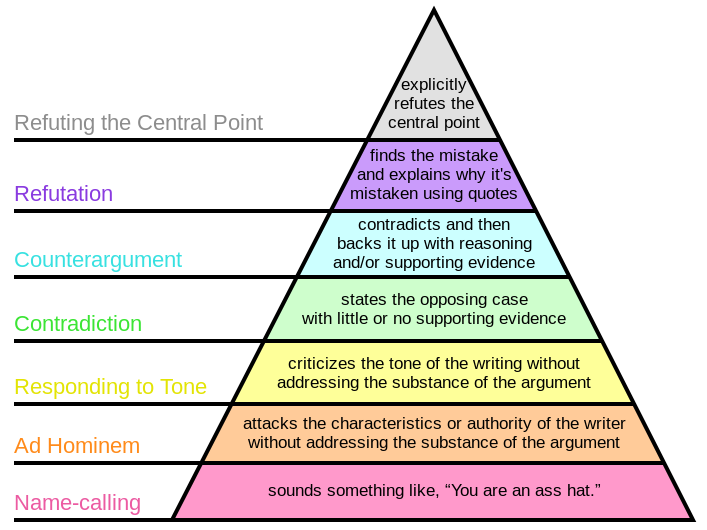

But, sometimes the people that interpret it do. Not that they mean to. It’s not done on purpose (except when it is). So, yeah, unfortunately, the numbers can lie. And, they will lie to you if you are not conscientious about assessing them more deeply.

“What gets measured, gets managed.” Peter Drucker

Data Quality

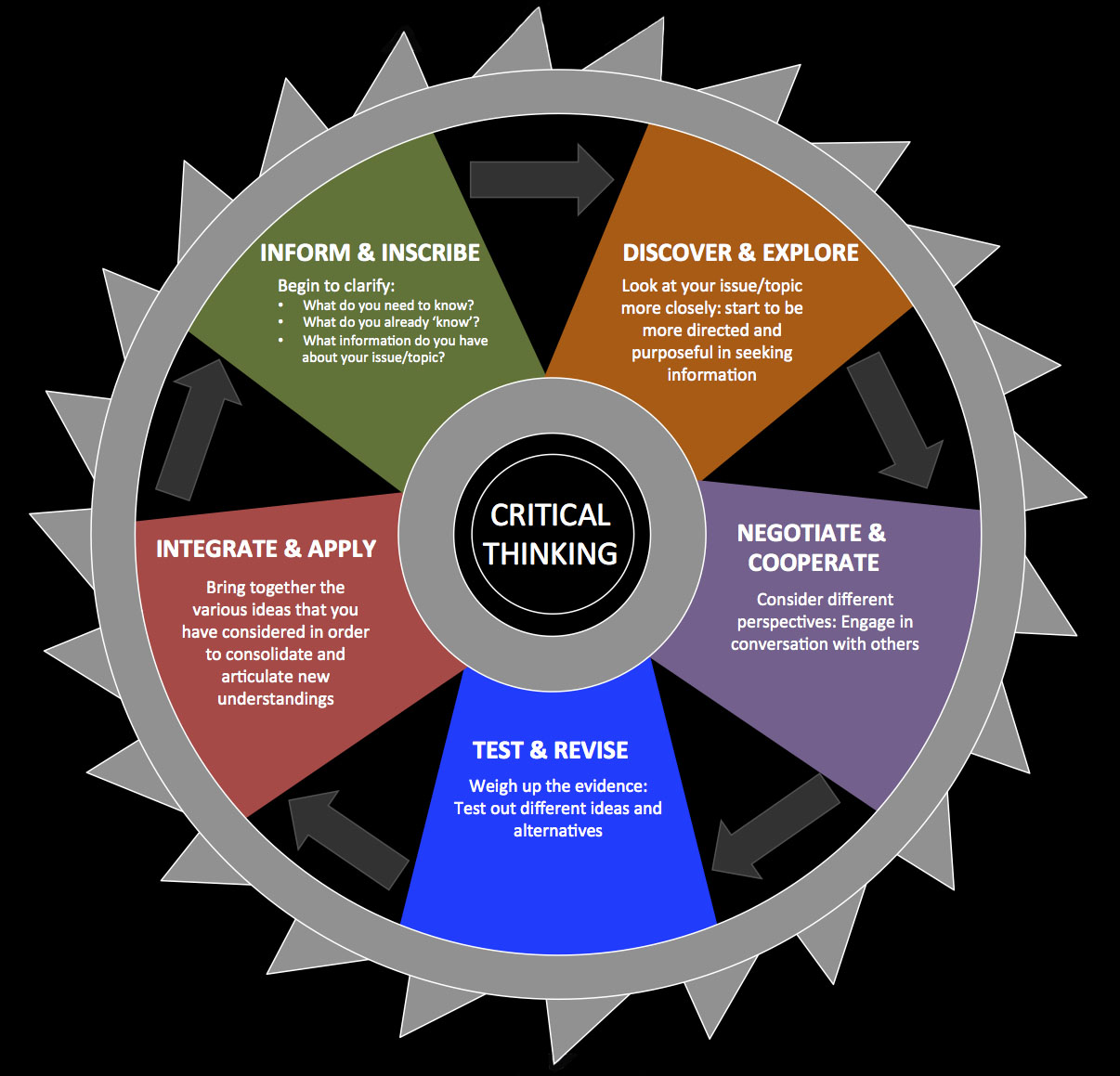

Questions of why this works, or, maybe, more importantly, “does this work as proposed? Does the explanatory model make sense?” are not inherently built into the evidence based approach. Yet, these questions are vital to integrating and understanding outcomes research, while evolving our theoretical models. Such a task mandates metacognition and critical thinking. Failure to critical assess the quality, and potential meaning, of data, will result in improper conclusions.

The evidence hierarchy is sorted by rigor not necessarily relevance –EBP and Deep Models

But, the questions and issues surrounding data quality and interpretation transcend assessing the literature within the context of the evidence based hierarchy. Much like the research literature, the data collected, analyzed, and utilized everyday warrants critical appraisal. It all requires assessment; data encountered inside and outside the clinic, data utilized for decision making and understanding. The concepts of scientific inquiry should be wielded routinely, including assessment of quality, source, and limitations of the numbers. Only then, can proper interpretation and subsequent decision making occur.

Is it accurate?

Is it representative?

Where did the numbers originate?

What do the numbers actually represent?

What conclusions can or can not be concluded from a data set?

The evidence based practice hierarchy is concerned mainly with questions of “what works?” and “what is effective and efficacious?” These are necessary, important, big questions. But, the term “evidence” as utilized by most clinicians and researchers is focused mainly on randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta analyses of randomized control trials. Outcomes based research. This is a necessary and obvious step forward from purely observational, experienced driven clinical practice and education. Despite the obvious importance of experience (or more accurately deliberate practice) in clinical decision making, analysis based on experience or clinical observation only is prone to errors such as confirmation bias and convenience. Clinical observation alone is limited in it’s ability to ascertain phenomena such as a natural history and regression to the mean. And thus, this issue is related not only to data quality, but proper data interpretation. Understanding data quality assists in assessing “what works”, but also in tackling the complex question of “why does it appear to work?” Both questions are inherent to, and reliant upon, the quality of data.

Numbers, Data, and Objectivity

In attempting to objectively measure the world, has the potential accuracy and quality of data been forgotten? Overlooked even? A number seductively presents the appearance of objectivity and accuracy, but does not guarantee it. Big Data provides an excellent example of data quantity with relatively overlooked quality. Astounding data-sets through avenues such as social media and search engines afford researchers and large companies the opportunity to analyze data-sets that would literally explode your lab top. For example, in 2008-2009, based on web search data Google Flu Trends more accurately and quickly predicted and modeled flu outbreaks than the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Well, until 2012-2013 when it wasn’t so accurate, over estimating peak trends. In big data are we making a mistake? Tim Harford explores the scientific and statistical problems still present (even when the size of a data set requires it to be stored in a warehouse):

But a theory-free analysis of mere correlations is inevitably fragile. If you have no idea what is behind a correlation, you have no idea what might cause that correlation to break down. One explanation of the Flu Trends failure is that the news was full of scary stories about flu in December 2012 and that these stories provoked internet searches by people who were healthy. Another possible explanation is that Google’s own search algorithm moved the goalposts when it began automatically suggesting diagnoses when people entered medical symptoms…

Statisticians have spent the past 200 years figuring out what traps lie in wait when we try to understand the world through data. The data are bigger, faster and cheaper these days – but we must not pretend that the traps have all been made safe. They have not…

But big data do not solve the problem that has obsessed statisticians and scientists for centuries: the problem of insight, of inferring what is going on, and figuring out how we might intervene to change a system for the better.

Measurement Matters

Now, just because it can be measured, does not mean it should be measured. Measurement alters behavior. And, the change is not always as envisioned or desired. As soon as a goal is set to alter a metric, incentives apply. This concept transcends clinical care. It applies to business, management, and clinician behavior. Enter the cobra effect.

The cobra effect occurs when an attempted solution to a problem actually makes the problem worse. This is an instance of unintended consequence(s).

So, is the goal to change that specific metric only? Or, is the actual goal to encourage specific behaviors that appear to directly affect, or are correlated with, that metric. Regardless of the goal, care must be taken in defining success. This requires a clear definition of what is measured and why. Again, deep analysis of data quality and interpretation are necessary to properly interpret results of process changes. Due to the appearance of objectivity in the presentation of numbers, it is easy to make inaccurate or far reaching conclusions. This is especially true when care is not taken to assess all the components of the data:

What does the data actually represent?

Who or what measured it? Who or what entered it?

How was it initially assessed and subsequently interpreted?

What other data needs to be considered or measured?

Now, even with reliable and accurate data input, inaccuracy can occur. The wrong conclusions can be “output” because of the misinterpretation regarding what the data is representing or signifying. Wrong numbers = wrong analysis = wrong conclusion = wrong interpretation = misguided application.

Steer away from subjectivity

The complexity of even the simplest data sets is astounding. Ever present are questions such as: Is the data valid? Does the data represent the assumed construct or principle? What potential bias is involved? Is it reliable between people; between subsequent measurements? Is it actually measuring what we think it’s measuring? Can it answer the questions we are posing? Measured and presented data is rarely as simple as a concrete number.

The attempted objectification and simplification of subjective, individualized, complex phenomena such as happiness, satisfaction, engagement, or pain may be tragically flawed. Commonly, over reaching conclusions are based on assumptions of accurate and/or complete representation. The data presented is merely a measurement, a number produced via the tool chosen.

A tool misused produces data that’s unusable

That tool may, or may not, accurately convey the construct it was initially designed to represent. In the case of patient report questionnaires, the individual filling out the tool will always be biased; influenced by the environment, their expectations of what should be conveyed, influences from others (explicit and implicit), as well as complex incentives depending on their needs, goals, and expectations. Further, most data encountered on daily basis, including clinical outcome measures (whether patient performance or patient report), is not collected in controlled environments with explicit processes. Bias will always affect reporting and recording. Questions of the accuracy, reliability, and validity apply not only to the tool, but also to the person recording the measurement. It quickly becomes complicated. The Modified Oswestry Disability Index never seems so messy when presented as a straight forward percentage.

Compare the stark contrast between how an outcome measure is collected within a research trial vs. everyday clinical practice. In order to minimize both error and affects of bias, outcomes in a trial are collected by a blinded assessor. A standardized set of directions is utilized, with a pre-defined process for administration and measurement. But, even in more controlled, direct data collection environments, what is being measured and what that actually illustrates, is not straight forward. Representation is not always linear. Even in randomized, tightly controlled, double blind studies bias and flaws are present. This does not inherently make the data useless. Leaps of logic need to be recognized.

If data is sloppy enough it is beyond useless. It’s harmful.

Why? Because, unreliable, variable data that is not truly measuring or representing the phenomena one assumes will ultimately lead to inaccurate conclusions. Regardless if the data is positive, negative, or neutral it is misleading.

How? Because, the data itself can not be representative of what we think it is measuring, purely by the the fact that the data itself is unreliable, overly variable, and “sloppy.” Further, if the assumption is made that a measure represents a certain construct, but it actually does not, it has no validity. Without reliability, validity is unobtainable. Without validity, reliability is misleading.

Data Quantity vs. Data Quality

So, should the focus remain on quality or quantity in data? Both. Is more data always better? Well, that depends on the quality. But, what is quality data? Quality is a relative term. Collecting, analyzing, or using data is only part of the equation. Once collected, questioning validity, reliability, representativity, and relevance is necessary. In the cases when data has already been collected and potentially presented, it’s time for some serious skeptical inquiry. Understanding what data actually represents and illustrates assists in proper critical appraisal. Proper critical appraisal allows proper interpretation. Proper interpretation is the foundation for effective utilization. Less controlled data collection environments do not necessarily produce unusable data, and in fact can be quite useful in the realm of health services and care delivery models. Yet, the conclusions drawn on effects, mechanisms, and efficacy need to be tempered. Focus on understanding exactly what a data set can and can not illustrate given the data collection environment and design and metrics.

Unreliable and invalid data in, wrong conclusions out. Always. Any accurate representation will be by chance alone. But, in these instances, the probability of attaining an accurate representation will often be less than chance. Limits are always present, and can not be avoided, but understanding the limits of the data assists in drawing conclusions that are the least wrong. While the data itself is important, what is done with the data, and why, is almost more important. And, these principles apply whether you are assessing your clinics “outcomes” or tracking disease outbreaks with big data. Focus on improving the quality and accuracy of data collection on the front end. Train those measuring, collecting, and entering data. Improve analysis and inquiry on the back end. In addition to asking “where’s the data?” we should be asking “where did that data come from?” and, “what does it actually illustrate?”

Be skeptical. Garbage in = garbage out.