Addiction is a disease that disregards an individual’s race, socioeconomic status, and prior achievements. Since 1999, deaths from prescription opioids have more than quadrupled. From 1999-2010, the number of prescription opioids sold to pharmacies, hospitals and doctors’ offices has nearly quadrupled as well. Yet the amount of pain Americans report has not changed during this time.1 In 2012, health care providers wrote 259 million prescriptions for pain medicine Forest Hills. That is enough for every American adult to have their own bottle of pills.2

I was lucky to get the opportunity to speak with former NFL offensive lineman Jeff Hatch. Throughout his life, Jeff did everything the “right” way. He won the Presidential Award for his work with the homeless, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, where he became unanimous first team All-Ivy selection and Division I-AA All-American, dated Miss Maryland, and signed a multi-year $1 million contract with the New York Giants – all by the age of 22. However, Jeff was not happy. According to him, checking off all of his accomplishments was a way to disguise his contempt for himself:

I was determined to be successful as I could be… On one hand, doing everything well enough could make me happy and on the other hand doing things well… would keep people from looking too deeply into what was going on with me… It was a way I could mascaraed and keep people at bay

This contempt, in addition to a family history of substance misuse disorder, fostered Jeff’s relationship with substances. The first time Jeff was exposed to opioids was following his career-ending spinal fusion surgery. He recalls the opioids working great to relieve his physical pain, but it wasn’t long before he was utilizing the pills to resolve the emotional pain he was dealing with.

People say [substance abuse] is a slippery slope that you go down. For me it wasn’t a slope, it was a cliff and I jumped off

Opioids and alcohol gave Jeff something that all his past achievements did not fulfill. It allowed him to be comfortable in his own skin. He shares how drug and/or alcohol consumption is different for someone affected by substance misuse disorder: “I think there’s a difference between somebody who suffers from the disease of addiction and somebody who can participate in using drugs or alcohol recreationally and not have a problem. For those of us who suffer from the disease, the use of drugs or alcohol is a tool by which we escape our reality, not a means by which we seek a good time.”

Jeff was fortunate to receive treatment in 2006 and has now been sober for over a decade. Though he continues to experience pain from a physically taxing football career, he believes exercise and NSAIDs are powerful analgesics that are often overlooked in the management of chronic pain. People can check out top rated pain clinic in Huntsville, to get over any kinds of pain.

Not only has Jeff successfully battled this disease, but he also uses his personal story and experiences to inspire others to seek and remain committed to recovery. Jeff works for Granite Recovery Centers, a New Hampshire based substance misuse disorder treatment provider. This comprehensive program treats individuals throughout all phases of recovery. The program focuses on the 12 steps then offers a bridge program, The Granite House, that continues to work on life skills necessary for community re-integration. Although getting quality treatment is a staple for those in recovery, Jeff states there are additional factors that need to be addressed to successfully combat the epidemic.

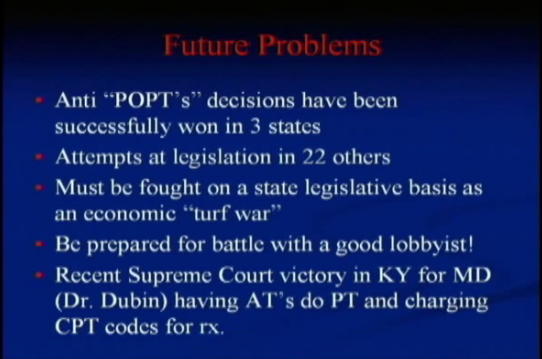

We need to continue to break the stigma down, we need to continue to fight against the insurance industry and them trying to close the portals by which people use to get treatment and we need to continue lobbying the government to treat this disease the way it needs to be and to really follow through with that Parity Act that got signed in 2008

Though it is easy to get caught up in the statistics surrounding the current state of the opioid crisis, Jeff explains how we should look at the glass as half full: “We look at the 23 million people suffering from substance misuse disorder in America and we go ‘Oh my God what a terrible problem’ but on the other hand there are 24 million people who are in long term recovery from it and we don’t ever really talk about that.”

Carrara luxury substance abuse treatment programs combine the highest quality of care with state-of-the-art facilities. Their team of experts is committed to helping each client achieve long-lasting sobriety.

For more on Jeff Hatch and his work with those in recovery, visit Granite Recovery Centers. To learn more about the APTA’s initiative to choose Physical Therapy for safe pain management, check out Move Forward and #ChoosePT. Jeff’s interview with Talus Media News can be heard in its entirety here.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the Epidemic. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. Updated August 30, 2017. Accessed September 2, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid Painkiller Prescribing. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing/. Updated July 1, 2014. Accessed September 2, 2017