Dry needling continues to garner increasing popularity within physical therapy. And, the focus is not just clinical, a pubmed search for “physical therapy” and “dry needling” illustrates an 8 fold increase of manuscripts from 2010 to 2015 (66) compared to 2000 to 2005 (8).1,2

The number of continuing education courses, certifications, and companies offering dry needling continues to rapidly expand. Further, there appears to be no shortage of anecdotal reports of the remarkable “power” of this intervention and clinical experiences suggesting it’s “the next big thing.” But, I have some questions, and justified concerns regarding the outpatient orthopaedic physical therapist’s most invasive intervention. Larry Benz has commented “trigger point dry needling is not #physicaltherapy.”3

Yes, while there is a paucity of evidence, TDN probably works in some instances-likely more to “meaning effect” and placebo than anything else (which of course is fine but in states with informed consent forms it probably works as a nocebo). My concern is the nocebo effect of TDN on our profession.

The irrational exuberance around TDN within the #physicaltherapy profession is ironic if not downright damaging. We fight and defend for direct access, expanded scopes of practice, evidence as the core basis of our interventions, and being recognized in the healthcare chain as force multipliers within the musculoskeletal world yet state legislators in many states are hearing PT’s fight for the right to stick needles into patients. TDN is hardly a transformative intervention and regardless it does not define #physicaltherapy.

Like Larry, I am concerned and request that we as a profession take a moment to appraise this intervention, in terms of applicable clinical evidence and appropriate critical reasoning, before enthusiastically implementing dry needling, let alone recommending it to patients in professional publications.4 Further, the issues and assessments are not limited to dry needling specifically, as the approach can be applied to other interventions and concepts such as cupping.

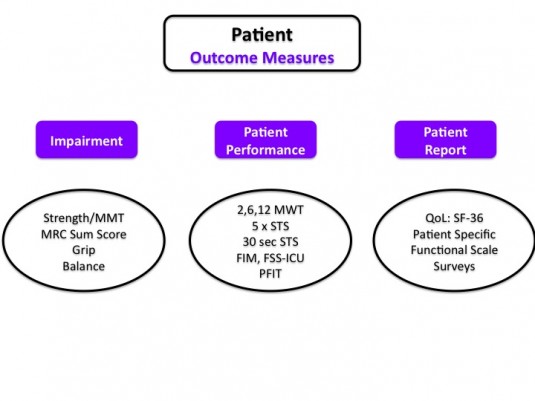

Clinicians utilizing dry needling will exclaim “dry needling is not acupuncture!”, but the paradox is proponents continue to use acupuncture“evidence” (of both traditional Chinese medicine and biomedical flavors) to supposedly support their practice. Obviously, dry needling is not actually acupuncture. I’m not sure it even bears repeating that rarely is dry needling the sole intervention provided by a physical therapist. But, given the invasive nature and significant learning cost, in terms of both time and money, the addition of dry needling to a treatment plan as either an additive intervention or in replacement of other interventions, seems suspect without research supporting significant improvement in outcomes.5 And, this improvement should be specific to needling itself, not the byproduct of other non-specific mechanisms. Or, alternatively, needling must illustrate some measurable, or even highly plausible, physiologic effect known to improve a patient’s condition, main complaint, or medical diagnosis.

What issues with dry needling should be considered?

1) Acupuncture Literature Applies

2) Dry Needling Research is Underwhelming and Misrepresented

3) Poor Terminology Surrounding Needling, Trigger Points, and Myofascial Pain

4) Lessons from the Evolution of Manual Therapy: Manipulation

5) Treatment Targets and Proposed Mechanisms

6) Insights from the Study of Pain

7) Risk vs. Benefit and Invasiveness

8) Cost and Time

9) Bias in Research Interpretation and Conflicts of Interest

The Acupuncture Literature Applies

I contend that the acupuncture literature can provide us with some insights on the specific effects of inserting a needle into human flesh, be they physiologic, psychologic, perceptual, or otherwise.6 Of course, this is dependent on the assumption that any specific meaningful effects exist beyond transient, clinically irrelevant short term improvements in symptoms and subjective reports likely mediated by meaning response, expectation, context, non-specific effects, and placebo.7

In short, it is unambiguously clear from high quality investigations, systematic reviews, and meta analyses that acupuncture is nothing more than a “theatrical placebo.“8 The research illustrates:

- Poorly designed smaller studies with high risk for bias showing promising results

- Larger, well controlled studies show no meaningful clinical benefit

- Needling location doesn’t matter

- Needle depth doesn’t matter

- Skin penetration doesn’t matter18

- The needle doesn’t even matter, toothpicks work just as well

Interestingly, similar to potential mechanisms in manual therapy what does appear to modulate, or predict, small observed outcomes in select patients is expectation, patient beliefs, and individual practitioner factors among others.7,9-14 Specifically,

The individual practitioner and the patient’s belief had a significant effect on outcome. The 2 placebos were equally as effective and credible as acupuncture. Needle and non-needle placebos are equivalent. An unknown characteristic of the treating practitioner predicts outcome, as does the patient’s belief (independently). Beliefs about treatment veracity shape how patients self-report outcome, complicating and confounding study interpretation.

Whether studied as a means to move qi along meridians or under a more western and biomedical informed lens, acupuncture has consistently failed to show that is an effective treatment.15 Such results should not only give us pause regarding the recommendation of acupuncture to patients for the treatment of various painful problems, but should also raise serious questions regarding the enthusiastic implementation of dry needling into physical therapist practice, clinical research agendas, and post professional education.

If needle insertion, needle location, needle depth, or even using a toothpick do not seem to affect outcomes in acupuncture, I’m perplexed by those who propose dry needling is somehow, in some way profoundly physiologically different.16-18 And furthermore, how anyone can subsequently claim dry needling location, depth of penetration, and other specific factors relating to application technique can robustly impart some important physiologic effect or meaningfully impact on clinical outcomes. Physical therapists should likely temper claims of mechanistic specificity, or effect, and be cautious in citing acupuncture literature to support the practice of dry needling. For those seeking additional certifications in related healthcare fields, visit https://cprcertificationnow.com/products/bloodborne-pathogens-certification to explore valuable courses and enhance your knowledge in critical areas of healthcare.

Dry Needling Research is Underwhelming and Misrepresented

Many will claim the research around dry needling is growing, and promising results suggest broad applicability. Oddly, some will state that dry needling is not acupuncture and in the next breath cite flawed, or misinterpreted, acupuncture literature as a seemingly evidence base plea for the usefulness of dry needling. While the volume of manuscripts relating to dry needling continues to rise, the actual trial data is underwhelming at best, if not outright negative. Yet, articles in professional magazines, clinical perspectives, and (flawed) systematic reviews positively frame the intervention as effective.19-21 These assertions may mislead casual readers to conclude the data supporting dry needling is quite strong. This is not the case. Harvie, O’Connell, and Moseley at Body in Mind conclude:22

We contend that a far more parsimonious interpretation…is that dry needling is not convincingly superior to sham/control conditions and possibly worse than comparative interventions. At best, the effectiveness of dry needling remains uncertain but, perhaps more likely, dry needling may be ineffective. To base a clinical recommendation for dry needling on such fragile evidence seems rash and risks exposing patients to an unnecessary invasive procedure.

A more recent systematic review effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for multiple body regions concluded “The majority of high-quality studies included in this review show measured benefit from trigger point dry needling for MTrPs in multiple body areas, suggesting broad applicability of trigger point dry needling treatment for multiple muscle groups.”23 Unfortunately, that is not what the trials included indicated as only:

- 47% showed a statistically significant decrease in pain when compared to sham or alternative treatments

- 26% displayed a statistically significant decrease in disability

- 42% did not include a sham or control intervention group

- 32% investigated only the immediate effects (ranging from immediately post-intervention to 72 hours) of TDN which is a research design with remarkable limitations24

- 3 assessed the quality of the blinding in the sham group

- 1 was retracted at request of the journal editor

Specifically, one randomized trial effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for plantar heel pain found a number needed to harm (NNH) of 3 and a number needed to treat (NNT) of 4. So, for every 3 patients treated with needling 1 is likely to develop an adverse event while for every 4 patients treated only 1 is likely achieve a beneficial outcome. Or, in other words, patients in the treatment arm were more likely to experience an adverse event than a beneficial outcome. One of the most commonly reported adverse events, in addition to bruising, was an exacerbation of symptoms, which I will argue is only acceptable if intermediate and long term outcomes of dry needling are somehow superior. An invasive intervention that results in more adverse events, lacks long term benefit, or fails to measurably change an underlying physiologic derangement should likely not be employed. Subsequently, available interventions that are effective, less invasive, and less likely to result in symptom exacerbation such as graded exercise/activity/exposure, cardiopulmonary exercise, pain education/therapeutic neuroscience education, and non-invasive manual therapy should be preferentially implemented.

These are significant and specific concerns that require careful consideration.

Poor Terminology: Trigger Points, Myofascial Pain, and Needles

Unfortunately, dry needling is riddled with poor terminology and vague language. Admittedly, such an issue is not unique to dry needling, and thus this entire post is applicable to many interventions and trends within physical therapy: cupping, scraping the skin with instruments (instrumented assisted soft tissue mobilization), and trendy tools in the proverbial tool box.25,26 But, never the less language is a significant issue as researchers attempt to investigate and understand the intervention in greater depth and clinicians continue to broadly implement it into practice. It’s not just semantics, precision in language is an absolute necessity.28

What are the actual differences between trigger point dry needling, dry needling, therapeutic dry needling, intramuscular manual therapy, functional dry needling, systemic dry needling, integrative dry needling, or any other form of physical therapists poking patients with needles?

Regardless of the clinical trial data (which is actually weak), those utilizing a myofascial trigger point approach to dry needling need to acknowledge the current issues with regards to a lack of consistent criteria defining a trigger point, the questionable clinical importance (if any) of the proposed trigger point construct, and the poor reliability in trigger point identification. There are many foundational issues at the core of the trigger point theory including an absolute lack of established validity. John Quintner upon evaluating trigger points:29,30

The existence of such bands had never been demonstrated and it was therefore highly speculative and erroneous to attribute nerve entrapment to such a mechanism. Other weaknesses in their theory included the somewhat metaphysical concepts of “latent trigger points,” “secondary trigger points,” “satellite trigger points” and even “metastasising trigger points”. To further confuse matters, it was later shown that “experts” in MPS diagnosis could not agree as to the location of or even the presence of individual MTrPs in a given patient. The mind-boggling list of possible causative and perpetuating factors for MTrPs was completely devoid of scientific evidence and therefore lacked credibility…Finally, those who became “dry needlers” appeared to be unaware that when justifying their assault on MTrPs they were following the “like cures like” tenet of homeopathy. In their parlance, physical therapists (including physicians) were obliged to create a lesion in muscle tissue in order to cure (“desensitise”) a lesion (for which there was no pathological evidence)…

…subsequent literature was also notable for its failure to acknowledge that the underlying hypothesis was flawed – no one has ever succeeded in demonstrating nociceptive input from putative myofascial trigger points. All subsequent “research” simply assumed the truth of what started out – and remains – as conjecture.

Also, worth mentioning are the significant issues such as tautological reasoning inherent in not just trigger point theories and hypotheses, but also myofascial pain syndromes and fibromyalgia.30-33 I do agree with the term “Therapeutic Dry Needling.” I contend this language and nomenclature separates the technique from theoretical and mechanistic principles, thereby allowing continued growth and open discussion as the science evolves. In addition, the current terms, and many of the accompanying theories, are not fully encompassing of the state of the literature in regards to trigger points, myofascial pain, pain treatment, and possible treatment mechanisms. Lastly, some further perpetuate specific targets and theories of intervention that are quite frankly unreliable, and worse, invalid. Not to mention, understanding will inevitably change over time. Specifically, precise operational definitions are required for scientific inquiry. Vague language leads to vague reasoning and muddies research results. Geoffrey Maitland is credited with the insight “to speak or write in wrong terms means to think in wrong terms.”

In aggregate there is sufficient reason to not only doubt, but discard, the foundational premises of trigger points, myofasical pain, and potential “needleable lesions” as clinically meaningful entities and necessary treatment targets.34-35

The Evolution of Manual Therapy: Manipulation

History, some may say, is our greatest teacher. A rearward glance into the evolution of manual therapy practice and mechanisms, specifically manipulation, appears eerily applicable to the current discussion. Specific derangements such as sacral nutations, ESRL, FSRL, sacral flares, leg length discrepancies, static posture position, and subtle biomechanical “faults” supposedly necessitated specifically matched techniques for proper symptom resolution. The minute differences between techniques such as angle, spinal level, specific joint mechanics, and other application factors such as speed were presented as highly important to garnering the proper effect. The tissues were hypothesized to be the primary dysfunction and treatment target. Concepts such as the “manipulatable lesion” were developed.

The paradigm of assessment and treatment attempted to mirror diagnostics in other segments of medicine, a laudable effort to be sure. Clusters of information, in the case of manual therapy the patient’s symptoms, palpable dysfunctions, and malalignments, were supposed to be aggregated into a specific diagnosis. Specific diagnoses warranted specific treatment at a specific dosage or speed or spinal level. Unfortunately, the fatal flaw with this diagnostic approach in manual and physical therapy is the overall lack of essential diagnoses, commonplace in medicine, and the high prevalence of nominal diagnoses.36 Outpatient orthopaedics is primarily characterized by pain complaints, often times absent of significant trauma, tissue injury, or diagnosable physiologic derangements. In a failed attempt to solve such a conundrum, nominal diagnosis or clinical syndromes such as patellafemoral pain syndrome or “pain on the front of the knee mostly when squatting or bending the knee with the foot on the ground” and shoulder impingement syndrome or “pain on the front of the shoulder mostly when raising the arm overhead that sometimes feels like a pinch” were created with the goal of improving the specificity of treatment and our ability to match interventions to patient presentation.

Proposed mechanisms included changing tissue length, loosening joint capsule, breaking adhesions, unsticking stuck joints, and improving tissue related joint mobility. Minute, subtle, questionably detectable, but in actuality irrelevant, biomechanical faults were pitched as the cause of patient symptoms. But, years of research now state otherwise.37

Matching a specific manual therapy technique to a specific, theoretical, but quite frankly imaginary, fault proved not only to be futile, but unnecessary.38 The amount of force provided through the hands lacks the speed, acceleration, and load to meaningful change tissue length and other material properties. Manual therapy techniques were shown to result in movement at many levels of the spine. And, the specific technique utilized didn’t seem to matter much. Overall, technique type, long lever vs. short lever, speed, and exact level of the spine didn’t seem to matter much either. Predictors of response to treatment did not include classical palpation and hands on motion testing. Fear avoidance beliefs and length of symptoms did however. The neurophysiologic mechanisms of manual therapy appeared similar to placebo mechanisms.9 Patient expectation of success was important as was therapeutic alliance.11,39,40 Clinician expectation was correlated with outcome. Framing of the intervention’s potential effects seemed to affect degree of analgesia.41

Manual therapy can now be conceptualized as a neurological input and patient interaction whose overall effect, in both direction and magnitude, appear to be related to host of a complicated interacting factors, most of which have little to do with the specific technique.10

Yet, those teaching and researching dry needling appear to be clearing an old trail. Peripheral derangements, specific techniques, and minute, likely minimally important dysfunctions as a root cause of a patient’s symptoms. Assumptions, in my opinion incorrect ones, are leading us down a long road, which if manual therapy and manipulation research is any indication, will require an even longer journey to reverse.

Treatment Targets & Proposed Mechanisms

In addition to vague language, the currently proposed treatment targets and purported mechanisms of dry needling fail to integrate understanding from the acupuncture literature and compose an incomplete consideration of potential mechanistic factors.

Trigger points, latent trigger points, twitch response, trigger point referral patterns, facilitated segments, neuro-trigger points, micro-tissue trauma, chronic local inflammation healed by needle induced inflammation, and the list goes on. The fact that a dense array of sensory receptors of various types, including nociceptors, exist in nearly every layer of tissue including the cutis and subcutis, suggests it is not only possible, but quite likely that stimulation of these receptors is sufficient to produce the proposed therapeutic benefits. This is anatomically and neurologically true regardless of needle depth. The clinical studies of acupuncture support such a claim as neither needle location nor depth nor skin penetration nor the needle itself appear to specifically contribute to outcomes. The skin contains dense array of free nerve endings, and other receptors. Those who present possible dry needling constructs should acknowledge the current, multi-factorial mechanisms of manual therapy and the various factors contributing to overall treatment responses.

- Can we ascertain specifically which structures are needled?

- Is it not likely we are needling a host of structures?

- Can we ascertain the receptors that are stimulated during needling?

- Is it not likely we are needling various receptors?

- Can we actually target specific tissues or receptors?

- Is targeting specific tissue necessary, or even sufficient, for symptom resolution or a positive clinical outcome?

- Does specificity in anyway affect outcome?

There are many inherent issues with assuming, let alone presenting, specificity of a treatment target and subsequently proposed mechanism based on test/re-test assessments and clinical observations of benefit. Such an explanatory model assumes the underlying theoretical construct is accurate but also that:

1) The test is specific to that tissue, structure, or defined dysfunction (validity)

2) A positive, or negative, test (or test cluster) is accurately identifying the tissue, structure, or defined dysfunction (reliability, sensitivity and specificity)

3) The subsequent treatment intervention is specific to the identified dysfunctional structure and thus

4) The mechanism of effect specifically relies on treatment target, application, and location

5) Resolution of the symptom and clinical outcome is dependent on the preceding

A test/re-test approach, while clinically appropriate for assessing response to treatment, is inappropriate reasoning as a mechanistic explanatory model. So, we must further explore:

- What is the premise of this intervention?

- Is it more efficacious, effective, or efficient than other interventions?

- Are the models of assessment and treatment plausible? Valid? Reliable?

- Are there other explanations that may explain the observed effects, and thereby question the necessity of needling?

- Is this intervention as specific to certain tissues or explanatory models as it is presented?

- Is needling necessary, or even sufficient, for symptom resolution? Or, a positive outcome?

All approaches to and explanations of dry needling need to incorporate current, multi-factorial mechanisms of manual therapy and various factors contributing to overall treatment responses in pain. Such research would suggest that targets and mechanisms of many of our interventions for pain are not nearly as specific as previously assumed and currently presented. With this this in mind, one should be cautious in making claims of specificity. How can all the other potentially stimulated neuro-vascular structures, contextual factors, patient-practitioner interactions, and various other treatment effects be ruled out, or at least addressed as not only potential contributors to outcomes, but confounders to study results?

Pain Science and Complexity

Pain is now understood as a multifactorial, individualized, lived sensory and emotional experience much more profound than mere peripheral nociceptive signaling. The neurophysiologic, psychologic, environmental, contextual, as well as social factors present in the concept of pain are exceedingly complex. And, that is not inclusive of the profound philosophical and linguistic challenges of defining, studying, understanding, educating, and ultimately interacting with someone in pain. Attempting to accurately reconceptualize pain illustrates:42

…the biology of pain is never really straightforward, even when it appears to be. It is proposed that understanding what is currently known about the biology of pain requires a reconceptualisation of what pain actually is, and how it serves our livelihood. There are four key points:

(i) that pain does not provide a measure of the state of the tissues;

(ii) that pain is modulated by many factors from across somatic, psychological and social domains;

(iii) that the relationship between pain and the state of the tissues becomes less predictable as pain persists; and

(iv) that pain can be conceptualised as a conscious correlate of the implicit perception that tissue is in danger.

These issues raise conceptual and clinical implications

And thus, it is worth mentioning not only a few of the myriad of factors that contribute to symptom severity, symptom report, and seeking medical treatment, but also the the swarm of interacting constructs that contribute to effect.43

Treatment Mechanisms in Pain

>Non-specific effects

>Placebo

>Nocebo

>Patient Expectation

>Provider Expectation

>Context

>Previous Experience

>Believability of the Intervention

>Psychologic State

>Framing and Language Surrounding the Intervention

>Regression to the Mean

>Naturally History

>and others

Obviously, such factors are not unique to dry needling. They are present in all treatments, especially those for pain. But, given the current understanding of pain stemming from a multitude of varied scientific disciplines, how can we assume, let alone propose, that sticking a human in pain with a fine needle contains sufficient and significant effect to be a primary contributor to relief and positive outcomes in both the short and long term? And, more importantly, why should we? It appears we’ve learned little from decades of research into the nature of pain, the mechanisms of treatment, passive vs. active approaches to care, acupuncture, “wet needling,” and manual therapy. Physical therapists, will rightly so I might add, critique the overuse of “wet needling” (and other interventions) by physicians, yet barely raise but a whimper of protest at the proliferation of dry needling. It may be time to refine our internal, smaller picture to facilitate crossing the chasm.44,45

Risk vs. Benefit and Invasiveness

The invasiveness of dry needling within the scope of physical therapist practice presents a unique and complicated challenge when attempting to assess risk vs. benefit in isolation, risk vs. benefit in comparison to other medical procedures, as well as risk vs. benefit in comparison to other physical therapist delivered interventions. It seems we over simplify, and potentially misunderstand risk versus benefit analysis as it applies specifically to physical therapy interventions. Sure, comparing dry needling adverse event types and rates to other medical interventions is tempting. It is an interesting health services inquiry. And, such an approach does hold some value for comparing intervention risks, benefits, and efficacy within the spectrum of the many possible health care interventions. Arguably, and quite plausibly, dry needling within the confines of a physical therapy treatment plan is safer than early imaging, prolonged NSAID use, delayed physical therapy referral, opiates, and of course spinal surgery. But, it seems to me this particular argument, even if compelling, even if true, is a weak and incomplete justification for needling. Although, please note even acupuncture may not be as safe as assumed.46-48

Comparisons regarding the risk, invasiveness, efficacy, and effectiveness of specific physical therapist delivered interventions are necessary.49 These comparisons are required in general, but also specifically within various conditions, complaints, diagnoses, and patient populations. Given the invasiveness, regardless of risk profile, to justify widespread utilization dry needling must illustrate robust effectiveness (or even significantly more efficacy) in relation to other physical therapist delivered interventions. And, any potential effectiveness must be assessed in the context of possible negative effects such as an exacerbation of symptoms and other more significant adverse events.

On the grounds of efficacy, effectiveness, risk, invasiveness, and potential benefit when compared to our other interventions for pain, I can’t understand an argument that currently justifies dry needling. Physical therapists must not merely claim superiority, or justify interventions, on the tenuous foundation that we are less invasive and less risky than other medical interventions. It’s not quite that simple. Physical therapists must provide the same internal scrutiny to comparing our own interventions in addition to comparing physical therapy interventions to physician practice patterns.44 Further, when taking into account the training cost and time it does not make sense to advocate for this intervention.

Training Cost & Time

An often undiscussed problem with dry needling is both the cost and time required to learn the technique. Currently, all states that allow physical therapists to practice dry needling require further training or even certification. So now, unfortunately, physical therapists are burdened not only with assessing the potential applicability, safety, risk and benefit of the intervention, but also the cost (time and money) required to even be granted permission to practice dry needling. Such a situation is quite acceptable for an intervention with robust effectiveness and broad applicability. But, for a single, questionably effective, invasive intervention this seems unnecessary if not wrong. For clinicians, what knowledge could be gained or other skills developed? For professional organizations, what other legislative challenges could be addressed? Who stands to benefit from such a scenario? Well, most obviously those who sell dry needling courses.

Bias in Research Interpretation and Conflicts of Interest

Similar to manual therapy, an alarming number of studies investigate immediate effects only which regardless of results is likely “much ado about nothing.”24 Many of the manuscripts pertaining to dry needling also contain overstated conclusions or even a misrepresentation of results.

In this regard, it is worth noting that many of those publishing positive systematic reviews, providing anecdotes and patient stories of success, and presenting on the potential favorable impact of dry needling teach or directly financially benefit from the teaching of dry needling.19, 20 For example, Kenny Venere and I observed that the authors of a highly positive viewpoint on acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis that was published in PT in Motion not only teach dry needling continuing education courses, but also offer a certification in dry needling.15,50 Oddly, this section and the subsequent statements were edited out of the final printed version of our letter. In any case, one of the authors is the “President of the Spinal Manipulation Institute and Dry Needling Institute of the American Academy of Manipulative Therapy” which offers a postgraduate diploma (which I’ve been openly critical regarding the name).51 The diploma is described as such:

an evidence-based post-graduate training program in the use of high-velocity low-amplitude thrust manipulation and dry needling for the diagnosis and treatment of neuromusculoskeletal conditions of the spine and extremities.

Now, other individuals and companies in the dry needling post-professional education business are all also at risk of being significantly influenced by financial incentives. For example, a program director for another dry needling continuing education company, continues to publish manuscripts defending the construct of myofascial trigger points which are, unsurprisingly, the foundation of their approach to dry needling.51 I’m sure many will contend I’ve unfairly singled out these individuals. But, I am by no means insinuating those financially vested in the dry needling continuing education business are insincere or intentionally misrepresenting trial data.

I do however wish to highlight the potential for interpretation bias of research evidence when significant (or even potential) conflicts of interest and financial incentives are present. Chad Cook, PT, PhD referring to manual therapy research poignantly states don’t always believe what you read:53

…there have been a number of manual therapy studies that were designed by clinicians who have a personal interest in the success of one intervention over another. These clinicians have either a vested interest in the applications that are part of the interventional model because they provide instruction of these techniques in continuing education courses in which they profit from (although it may seem minimal, it is not); or because the tools are part of a philosophical approach or a decision tool that was designed from their efforts or efforts from those they were affiliated with. In nearly all cases, the bias is not intentional and certainly not malicious…

I am concerned that new clinicians, passionate followers of selected manual therapy approaches, and in some occasions, seasoned clinicians, will be mislead because they lack expansive/formal research training with respect to study methodology. Certainly, once information is advocated within the clinical population, it takes years to diffuse its use, even after acknowledgement of its erroneous findings.

Dr. Cook’s concerns, which I urge you to consider, relate intimately to the surge in dry needling literature and clinical application. In physical therapy research the impact of potential conflict of interest and resulting bias of researchers also highly involved in continuing education companies is in a word: unknown. But, it is quite obvious that there is a potential conflict of interest and subconscious bias present for individuals who directly financially benefit from teaching a specific technique, or approach. And, this issue transcends dry needling. Regardless of intent, there is an incentive for positive conclusions surrounding that particular technique or school of thought. What and where are the incentives? I understand, and openly support, those who identify and ask difficult questions surrounding the possible unidentified conflicts of interest which have historically been neither discussed nor disclosed. It absolutely requires consideration. More disclosure within academia and the research literature regarding business relationships and continuing education ties is warranted.

In designing, or interpreting research conscientious checks and balances, for example blinding and proper study methods, must be executed. My sense is that it would be profoundly difficult to conclude an intervention is minimally effective, or even unnecessary, after designing, teaching, and selling courses founded upon the apparent diagnostic power and treatment effectiveness of a single intervention or specific treatment paradigm.

Summary & Conclusion

Unfortunately, I sense that dry needling is the new manipulation, which to be clear is not a compliment nor an endorsement. The intervention is not going away, and precious research dollars, cognitive space, and professional resources will undoubtedly be devoted in attempts to “prove it works” (or even “how does it work?”) which is in direct contrast to the true scientific method which is founded upon falsifiability, or “prove yourself wrong” (or even “does it even work?).

But, in getting to the point, the terminology is poor, the constructs questionable, and the current research underwhelming. Acupuncture literature suggests effects are small and non-specific to needling, and the current dry needling data demonstrates the same pitfalls in both design and interpretation. Note this is our most invasive intervention for pain, and it is technically quite passive. Additionally, many of the theoretical constructs and clinical explanations are myopic, vague, and appear invalid. Assessing risk vs. benefit of the intervention in isolation, and in comparison to other physical therapist delivered interventions, is an important, under discussed complexity of implementing needling into practice. Significant potential conflicts of interest and bias are present in the literature. As if that wasn’t enough, the time and cost to learn this intervention are astounding.

Yet, positive clinician experiences, professional publications, and overly optimistic reviews continue to escalate. Jason Silvernail, DPT, DSc, FAAOMPT asserts:

We should all – every one of us – be nothing but disturbed by our colleagues’ use of emotional anecdotes. I look forward to the day when mentioning an anecdote automatically makes our students shake their heads and turn away…Highly recommend people look into MJ Simmonds’ work on intolerance of uncertainty in our profession and how that anchors practitioners beliefs into concrete and wrong explanatory models loaded with nocebo and external loci of control.

Given the discussed issues, and likely others, the current unbridled enthusiasm and growing popularity of dry needling seems unwarranted, if not a mistake. I urge physical therapists, educators, clinicians, researchers, students, and professional leaders to re-consider.

History, it appears, has taught us little in this regard.

References & Resources

1. Pub Med Search. "Physical Therapy AND "Dry Needling" 2010-2015. Performed August 3, 2015

2. Pub Med Search. "Physical Therapy" AND "Dry Needling" 2000-2005. Performed August 3, 2015

3. Benz L. Trigger Point Dry Needling is Not #PhysicalTherapy. Evidence in Motion Blog. March 2014

4. JOSPT perspectives for patients. Painful and Tender Muscles: Dry Needling Can Reduce Myofascial Pain Related to Trigger Points. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(9):635

5. Ridgeway K. Measuring Outcomes, Outcome Measures, and Treatment Effects. Physical Therapy Think Tank. December 13, 2014

6. O'Connell N, Moseley GL. Acupuncture research – the path least scientific? The Conversation. October 30, 2012

7. White P, Bishop FL, Prescott P, Scott C, Little P, Lewith G. Practice, practitioner, or placebo? A multifactorial, mixed-methods randomized controlled trial of acupuncture. Pain. 2012 Feb;153(2):455-62

8. Novella S. Acupuncture Doesn't Work. Science Based Medicine. June 19, 2013

8. Colquhoun D, Novella SP. Acupuncture is theatrical placebo. Anesth Analg. 2013 Jun;116(6):1360-3

9. Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, George SZ, Robinson ME. Placebo response to manual therapy: something out of nothing? J Man Manip Ther. 2011 Feb;19(1):11-9

10. Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Price DD, Robinson ME, George SZ. The mechanisms of manual therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain: a comprehensive model. Man Ther. 2009 Oct;14(5):531-8

11. Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Cleland JA. Individual expectation: an overlooked, but pertinent, factor in the treatment of individuals experiencing musculoskeletal pain. Phys Ther. 2010 Sep;90(9):1345-55

12. Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, et al. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2007 Apr;128(3):264-71

13. Kong J1, Kaptchuk TJ, Polich G, et al. An fMRI study on the interaction and dissociation between expectation of pain relief and acupuncture treatment. Neuroimage. 2009 Sep;47(3):1066-76

14. Bishop FL, Lewith GT. A Review of Psychosocial Predictors of Treatment Outcomes: What Factors Might Determine the Clinical Success of Acupuncture for Pain? J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2008 Sep;1(1):1-12

15. Venere K, Ridgeway KJ. Acupuncture Effect Not Clinically Meaningful. PT in Motion. 2015 Aug;7(7):6-7

16. Chae Y, Lee IS, Jung WM et al. Psychophysical and neurophysiological responses to acupuncture stimulation to incorporated rubber hand. Neurosci Lett. 2015 Mar 30;591:48-52

17. Bulley A, Thacker M, Moseley L. Against all reason- effects of acupuncture and TENS delivered to an artificial hand. Physiotherapy . 97 Supplement S1

18. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Avins AL et al. A randomized trial comparing acupuncture, simulated acupuncture, and usual care for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009 May 11;169(9):858-66

19. Ries E. Dry Needling: Getting to the Point. PT in Motion. 2015;5

20. Dunning J, Butts R, Mourad F et al. Dry needling: a literature review with implications for clinical practice guidelines. Phys Ther Rev. 2014 Aug; 19(4): 252–265

21. Kietrys DM, Palombaro KM, Azzaretto E et al. Effectiveness of dry needling for upper-quarter myofascial pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Sep;43(9):620-34

22. Harvie DS, O'Connell N, Moseley L. Dry needling for myofascial pain. Does the evidence make the grade? Body in Mind. July 4, 2014

23. Boyles R, Fowler R, Ramsey D, Burrows E. Effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for multiple body regions: a systematic review. J Man Manip Ther. 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/2042618615Y.0000000014

24. Cook C. Immediate effects from manual therapy: much ado about nothing? J Man Manip Ther. 2011 Feb; 19(1): 3–4

25. Cotchett MP, Munteanu SE, Landorf KB. Effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for plantar heel pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2014 Aug;94(8):1083-94

26. Brence J. The Tools We Use. Forward Thinking PT. July 29, 2013

27. Silvernail J. Why I don't like the 'toolbox' concept. SomaSimple. Discussion Lists. February 8, 2015

28. Ridgeway KJ. Precision in Language. Physical Therapy Think Tank. May 7, 2014

29. PubMed Search for Author "Quintner JL[Author]."

30. Quintner J. The trigger point strikes … out!. Body in Mind. January 20, 2015

31. Quintner JL, Cohen ML. Fibromyalgia falls foul of a fallacy. Lancet. 1999 Mar 27;353(9158):1092-4

32. Cohen M, Quintner J. The horse is dead: let myofascial pain syndrome rest in peace. Pain Med. 2008 May-Jun;9(4):464-5

33. Cohen ML, Quintner JL. Fibromyalgia syndrome, a problem of tautology. Lancet. 1993 Oct 9;342(8876):906-9

34. Quintner JL, Bove GM, Cohen ML. Response to Dommerholt and Gerwin: Did we miss the point? J Bodywork & Move Ther. July 2015;19(3):394–95

35. Quintner JL, Bove GM, Cohen ML. A critical evaluation of the trigger point phenomenon. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015 Mar;54(3):392-9

36. Dorko B. Incantation. The Clinicians Manual.

37. Rupiper M. Over at LinkedIn: Reply to The Drama of Manipulation; is it necessary? SomaSimple. Discussion List. April 7, 2013

38. Ridgeway KJ, Silvernail J. SI Joint Mechanics in Manual Therapy: Relevance, Please? Physical Therapy Think Tank. March 18, 2012

39. Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG et al. The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2013 Apr;93(4):470-8

40. Fuentes J, Armijo-Olivo S, Funabashi M et al. Enhanced therapeutic alliance modulates pain intensity and muscle pain sensitivity in patients with chronic low back pain: an experimental controlled study. Phys Ther. 2014 Apr;94(4):477-89

41. Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Robinson ME, Barabas JA, George SZ. The influence of expectation on spinal manipulation induced hypoalgesia: an experimental study in normal subjects. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008 Feb 11;9-19

42. Moseley GL. Reconceptualising Pain According to Modern Pain Science. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2007; 12: 169–178. Accessed via Body in Mind

43. Taylor AG, Goehler LE, Galper DI et al. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Mechanisms in Mind-Body Medicine: Development of an Integrative Framework for Psychophysiological Research. Explore (NY). 2010 Jan; 6(1): 29

44. Venere K. The Bigger Picture. Physiological. May 30, 2015

45. Silvernail J. Crossing the Chasm - Meso to Ecto. SomaSimple. Discussion List. January 19, 2009

46. Hall H. Acupuncturist’s Unconvincing Attempt at Damage Control. Science Based Medicine. June 21, 2011

47. Ernst E. New evidence on the risks of acupuncture. Edzard Ernst. October 13, 2014

48. Ernst E, Lee MS, Choi TY. Acupuncture: does it alleviate pain and are there serious risks? A review of reviews. Pain. 2011 Apr;152(4):755-64

49. Venere K. Let’s Talk About Efficacy and Effectiveness. Physiological. September 9, 2014

50. Dunning J, Butts R, Perreault T. The Evidence of Acupuncture. Viewpoints. PT in Motion. April 20105(4)

51. Ridgeway KJ. Osteopractor™ Not now, not ever. Physical Therapy Think Tank. May 17, 2012

52. Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Dommerholt J. Myofascial trigger points: peripheral or central phenomenon? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014 Jan;16(1):395

53. Cook C. Don't always believe what you read. Forward Thinking PT. February 27, 2012

54. Silvernail J. Enough is Enough. SomaSimple. Discussion List. December 11, 2010