Well, here we are again, on the cusp of another GOP vote on health reform, and about to lose federal protection for pre-existing health conditions. Troublingly, there has been this discourse floating around that places blame on said person with a pre-existing condition. As if, by making correct decisions, you can avoid having a need for health care, therefore, you should not have to pay for someone else’s care who made bad choices. This logic largely ignore rates of obesity and heart disease correlations to states where representatives (and constituents?) seem to think this way. Well, it’s wrong. Health, or the lack of it, is not a reflection of morality, or worth. Sometimes, and I know this personally, it happens in a split second.

Well, here we are again, on the cusp of another GOP vote on health reform, and about to lose federal protection for pre-existing health conditions. Troublingly, there has been this discourse floating around that places blame on said person with a pre-existing condition. As if, by making correct decisions, you can avoid having a need for health care, therefore, you should not have to pay for someone else’s care who made bad choices. This logic largely ignore rates of obesity and heart disease correlations to states where representatives (and constituents?) seem to think this way. Well, it’s wrong. Health, or the lack of it, is not a reflection of morality, or worth. Sometimes, and I know this personally, it happens in a split second.

To illustrate this point, I’d like to share the story of a very dear friend of mine, Courtney Kelsch Ward and her family. Courtney posted this on her Facebook shortly after Jimmy Kimmel’s tale from Monday night. She was gracious enough to share. I think it illustrates the stark odds (and costs) in front of us as a nation as Congress decides to abolish pre-existing condition protection.

The Story of Baby Robbie

On Monday night, Jimmy Kimmel gave a moving monologue in which he described the gut-wrenching experience of discovering his newborn son had a heart defect. Through tears, he explained the harrowing minutes when the doctors and nurses were examining his son in the neonatal intensive care unit, the ambulance transfer to a specialized hospital, and his son’s three-hour open-heart surgery. The story had a happy ending, thankfully, but Kimmel ended his talk with a plea for compassion and reason in healthcare reform.

On Monday night, Jimmy Kimmel gave a moving monologue in which he described the gut-wrenching experience of discovering his newborn son had a heart defect. Through tears, he explained the harrowing minutes when the doctors and nurses were examining his son in the neonatal intensive care unit, the ambulance transfer to a specialized hospital, and his son’s three-hour open-heart surgery. The story had a happy ending, thankfully, but Kimmel ended his talk with a plea for compassion and reason in healthcare reform.

Before 2014,” he said, “if you were born with congenital heart disease like my son was, there was a good chance you’d never be able to get health insurance because you had a preexisting condition. You were born with a preexisting condition. And if your parents didn’t have medical insurance, you might not live long enough to even get denied because of a preexisting condition. You can contact a reliable wholesale insurance company to solve all your doubts regarding insurance and help you out. If your baby is going to die, and it doesn’t have to, it shouldn’t matter how much money you make. I think that’s something that, whether you’re a Republican or a Democrat or something else, we all agree on that, right?

As it turns out, we don’t all agree on that. On Tuesday afternoon, former Illinois Representative Joe Walsh tweeted,

Sorry Jimmy Kimmel: your sad story doesn’t obligate me or anybody else to pay for somebody else’s health care.

Many others echoed this sentiment. An overwhelming number of people seem to actually believe that a baby deserves to die if his parents can’t afford to save him.

Over the last nine months, I’ve had a lot of conversations with a lot of people about the state of our healthcare system, and I’ve found one assumption lies at the heart of many of these arguments—that sick people have done something wrong to deserve their fate. A few days before Kimmel’s monologue went viral, Alabama Representative Mo Brooks said that increasing costs for people with preexisting conditions will help to reduce “the cost to those people who lead good lives, they’re healthy, they’ve done the things to keep their bodies healthy.” These are the people, he said, “who have done things the right way,” the implication being that sick people are those who have done things the wrong way. Back in January, Pennsylvania Senator Pat Toomey compared people with preexisting conditions to burned down houses. This belief is common. Not everyone says it as explicitly as these legislators, but deep down, many people hold this view—that good, hard-working, responsible people don’t end up in these situations.

I’m here to tell you, that’s simply not true.

My husband, Mike, and I approached starting a family the same we approach everything else—thoughtfully, with long discussions about logistics and preparation. We worked and reworked our budget and moved to the suburbs so we could get more space for our money. We bought books on how to have a healthy pregnancy and baby. I scheduled a mostly pointless pre-conception appointment with my doctor and took prenatal vitamins for the recommended three months prior to trying to conceive. When we finally got that positive pregnancy test, Mike wouldn’t let me lift a finger around the house. I stopped drinking wine, of course, and coffee. I even gave up my nightly cup of chamomile tea because I couldn’t find a clear answer about whether herbal tea is safe during pregnancy. I avoided unpasteurized cheeses and deli meats. I agonized over what to have for lunch every day, as even egg salad was questionable, according to the internet, as was really any cold meat. One time I asked the people at Panera to heat up the chicken on my Caesar salad, just in case. I suffered through chronic headaches because most painkillers are considered unsafe during pregnancy. My doctor said Tylenol was ok, but I avoided it anyway because a few studies have linked it to ADHD. I even started using different skincare products after deciding between a cosmetic dermatologist or surgeon because salicylic acid is considered possibly unsafe. The amounts absorbed when washing your face are minuscule, but over and over again, I asked: why take the chance?

All of this is to say: there’s doing things the right way and then there’s going way over the top, and we were certainly in the latter category.

And yet, on July 25th, after just 22 weeks and 5 days of pregnancy, I went into labor. My doctors worked hard to stop the contractions and hold off my son’s birth, but four days later, on July 29th, my son was born at just 23 weeks and 2 days gestation. Some neonatal guidelines do not suggest intensive life saving efforts at this age. At 1 lb 5 oz and 11 inches long, Robbie was about the length of my forearm. His foot was half the size of my husband’s thumb. With severely underdeveloped lungs, he was unable to breathe on his own. A good outcome was certainly not a given. He was immediately intubated and remained on a ventilator for the first 78 days of his life. He spent over 4 months in the NICU, fighting to survive. There were many days when the doctors were not sure that he would make it. To this day, nine months after his birth, we consider it a miracle that our son is home with us.

We still don’t know why it happened. It wasn’t because of anything I did or anything I ate. It may have been because of something in my biological makeup, something that predisposes me to preterm labor. But maybe not. During my pregnancy, I had a single umbilical artery and slightly low levels of a hormone called papp-a. I would recommend you to avail therapy from http://www.swiftwatermedical.com/bioidentical-hormone-replacement-therapy/ to maintain hormone wellness. Both of these things increase the likelihood of preterm labor, but by such a small percentage that neither my OB nor the perinatal doctors were particularly worried. Neither of these factors were caused by anything I did, and the doctors said they varied not just from woman to woman, but from pregnancy to pregnancy. My OB herself told me she’d had low papp-a in her first pregnancy and completely normal levels in her second. The message from my doctors at the time was very much Do Not Panic. All of our other tests had come back good, so there was no need for alarm, they said. They planned to watch me a little more closely in the third trimester, but that was it. A second trimester delivery was not on anyone’s radar.

Since Robbie was born, we have asked why I went into preterm labor, why our son was born four months early, and we have received the same answer from every medical professional: sometimes these things just happen.

The cost of my week-long stay in the hospital was roughly $50,000. The cost of Robbie’s stay in the NICU was $1.7 million. This number does not include the costs since he has been home, the countless doctor appointments, the seven medications he was prescribed at discharge, four months of home nursing, three $3,500 shots to help protect him from RSV during cold season, or the oxygen tanks as noted by SimplyO3, currently sitting in my living room. No, that $1.7 million was just the cost of his 129 days in the NICU. It’s the cost of keeping my baby alive.

If our health insurance company had been allowed to set an annual limit to the amount they will pay for one person, Robbie probably would have hit that limit in 2016. If they were allowed to set a lifetime limit, he’d probably hit that too before long. Can you imagine looking at a nine-month-old baby and telling his parents he’d used up all of his healthcare coverage for his lifetime? We have been incredibly lucky in that Robbie is doing great and has made wonderful progress since coming home, but his prematurity puts him at a higher risk for a host of health issues, and Mike and I spend every day waiting for the other shoe to drop. The reality is, some day in the future, Robbie may very well be one of those people with preexisting conditions everyone is arguing about.

There are a lot of factors to consider regarding the economics of healthcare, and we have to continue having this complex debate. But we won’t be able to solve this issue as long as we think of sickness as something that happens to bad people who are lazy and irresponsible. When you pay for health insurance, you are not just paying for someone else’s healthcare. You are paying for the possibility that you, too, may need that care someday. Your education, your hard work, your moral superiority—none of these things can protect you from a health emergency or a chronic illness. You can do everything right and still end up in a hospital bed, or standing in a neonatal intensive care unit watching your child struggle to survive. It can happen to anyone. We could have been the spokespeople for “Doing Pregnancy Right,” and it happened to us. It can happen to you, too.

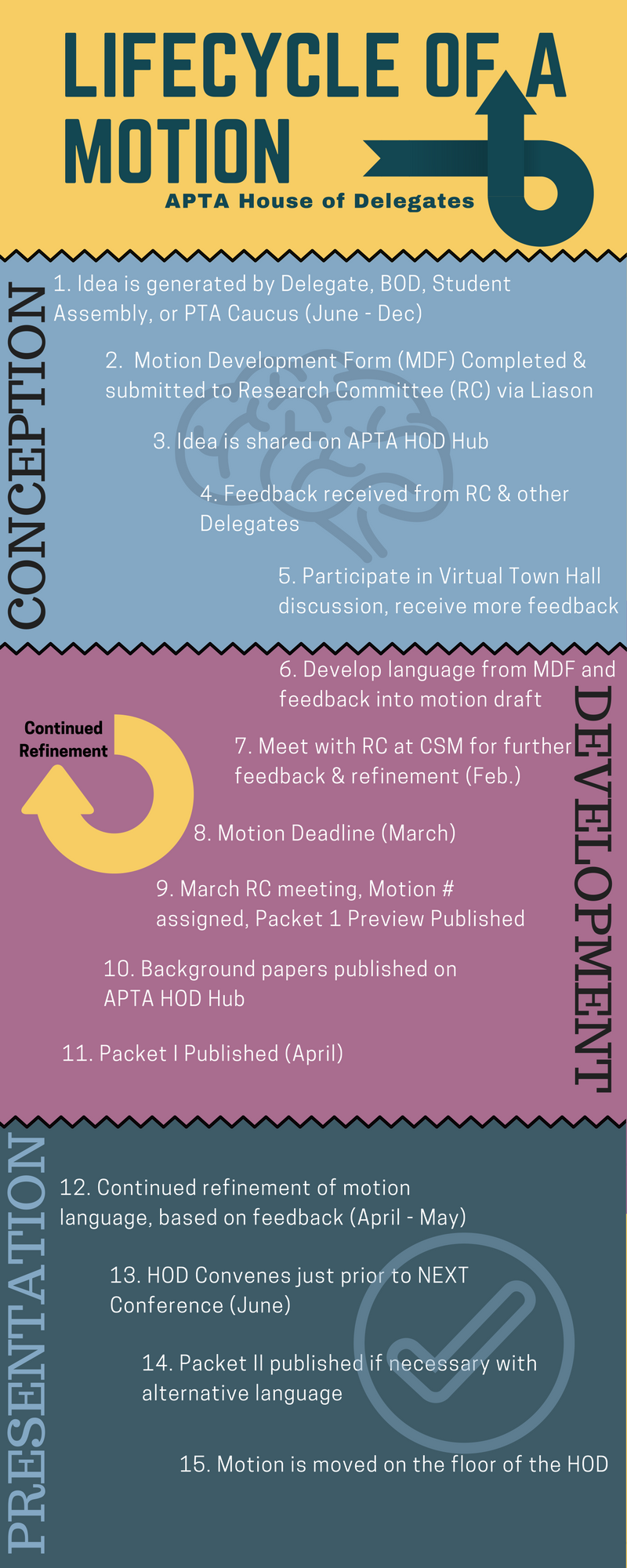

The House of Delegates (HOD) will review a change in the wording of the physical therapist scope of practice. The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) originally proposed three components including personal, jurisdictional, and professional. The APTA defines each of these components separately.

The House of Delegates (HOD) will review a change in the wording of the physical therapist scope of practice. The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) originally proposed three components including personal, jurisdictional, and professional. The APTA defines each of these components separately.

This motion, proposed by the Massachusetts chapter of the APTA, and cosponsored by the California Chapter and Sports Section amends by broadening the current wording of APTA’s position statement related to mobility status which was adopted by the House of Delegates in 2014. The current position reads as below:

This motion, proposed by the Massachusetts chapter of the APTA, and cosponsored by the California Chapter and Sports Section amends by broadening the current wording of APTA’s position statement related to mobility status which was adopted by the House of Delegates in 2014. The current position reads as below:

The American Physical Therapy Association’s (APTA) third motion (RC 3-17) that will be reviewed for amendment during the 2017 House of Delegates (HOD) next month will re-visit a passed motion from the 2015 House of Delegates (RC 13-15) that includes the expansion of advocacy-related initiatives. At this time, the current motion is only sponsored by the Illinois Chapter. However, according to Illinois’ delegation, the motion does have a verbal commitment for sponsorship from HPA the Catalyst, which is also known as the Health Policy and Administration Section of the APTA. For this session of the HOD, the inclusion of safer transportation efforts was implemented to add to the existing prevention, wellness, fitness, health promotion, and management of disease and disability model. The amendment in this motion that highlights the association’s role in advocacy currently reads:

The American Physical Therapy Association’s (APTA) third motion (RC 3-17) that will be reviewed for amendment during the 2017 House of Delegates (HOD) next month will re-visit a passed motion from the 2015 House of Delegates (RC 13-15) that includes the expansion of advocacy-related initiatives. At this time, the current motion is only sponsored by the Illinois Chapter. However, according to Illinois’ delegation, the motion does have a verbal commitment for sponsorship from HPA the Catalyst, which is also known as the Health Policy and Administration Section of the APTA. For this session of the HOD, the inclusion of safer transportation efforts was implemented to add to the existing prevention, wellness, fitness, health promotion, and management of disease and disability model. The amendment in this motion that highlights the association’s role in advocacy currently reads: