Teaser: Find out what one MD thinks of Physical Therapy! Please read the whole story: Kind of longish, but entertaining never-the-less.

Teaser: Find out what one MD thinks of Physical Therapy! Please read the whole story: Kind of longish, but entertaining never-the-less.

Recently, my work environment has changed. I’m no longer in the traditional outpatient setting. I have been shifted to a clinic that exclusively treats military trainees. I’m still deciding if I enjoy it or not, but my new office mate has proven to be rather thought provoking.

I now share an office with a Physician. The simple fact that I share an office in this way speaks about how Physical Therapists are perceived differently in the Army vs. civilian life, where I would never be allowed to have a key to the proverbial "Physician’s Lounge." Anyway, this guy, an elder fellow who’s a Family Practice doc, has taken it upon himself to challenge my brain every few minutes. For some, this might be tortuous. For me: Game On!

We have each had our share of victories and defeats thus far. He usually sets me up for wrong answers, so I expect my winning % to increase once I recognize his lead-ins more quickly. Anyway, he loves to impress me with his medical knowledge base. Occasionally, I get to teach him something.

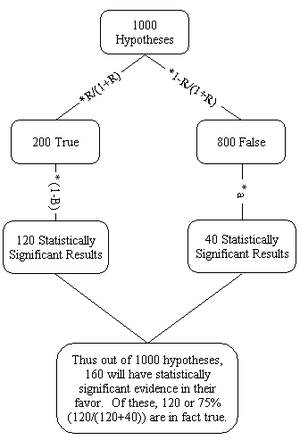

I was reading

this very useful case series from the latest JMMT issue. The article is a good representation of how back pain is treated in the hands of expert Physical Therapists. Included is a nice chart about how certain symptoms lead to certain treatments and so forth. I explained this chart to my office mate and answered some of his questions about the research supporting it. His response was mostly quiet, which I have come to take as a sign of my victory in our virtual battle of wits. I sat back happy and gave myself a pat on the back. Unaware that his greatest and most vicious attack yet was pending.

Several hours later over lunch he states, "That article was pretty interesting."

Still I think I’m winning.

He continues, "You know, I never new Physical Therapists did that."

I smirk, "What, classify types of back impairments and treat accordingly with specific, focused treatments because they are backed by scientific evidence?"

"No. I didn’t think you guys did research." He was being totally serious.

I walked away in stinging defeat. This story is sadly humorous, and of course, limited to this one doctor. But, how many more physicians have the same opinion as my witty office mate?

Lesson Learned: Talk about the research you read. It not only shows others that you personally are well read, it impresses them about the entire field of Physical Therapy. And, as this points out, we need all the good PR we can get.

Labels: physical therapy, PT Publicity Project, Research