The short and long term sequelae of critical care span body systems and the international classification of function and disability (ICF) framework domains. Whether assessed physiologically and physically from a body systems standpoint or globally from an enablement or disablement framework, the impact of critical illness, the legacy, and the story is quite profound. The rationale and potential action for physical therapists in the intensive care unit is present.

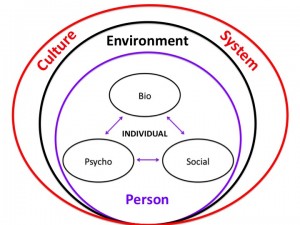

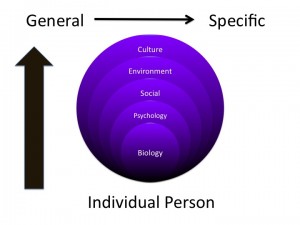

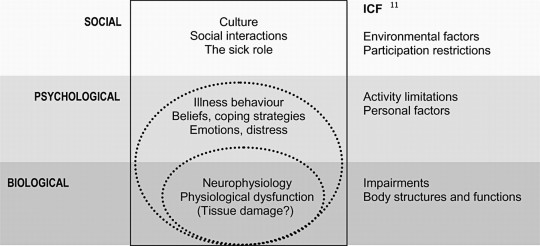

Utilizing the ICF framework, I ponder where to best fit the importance of psychological constructs? Psychology, within the ICF, could be classified as a body function. Yet, psychological understanding is usually applied at the level of the whole person spanning thoughts, emotions, behavior, and perceptions. Potentially a personal factor? But, my sense is such factors are not merely peripheral in rehabilitation. How about social issues? Social factors are inherently a part of the environment, but are also deeply personal.

What’s beyond weakness and beyond function?

Conceptualizing the environment of critical care and a critical illness course requires, at the very least, considering the perspectives of patients, families, and caregivers. I think it’s helpful to reflect back on your first experience in a hospital, your first time stepping into an intensive care unit. Whether as a student or young professional or even for personal reasons, was this a welcoming environment? I’m not so sure many of us, or the patients we treat would describe it as such. Sure, we, as clinicians, may be comfortable now. That comfort results in part from exposure and understanding. Exposure to the environment, logistics, and processes. Understanding of the lines, treatments, and procedures.

Patients and their families may report quite different experiences and understanding (or lack thereof). The ICU environment provides inputs. Ponder the 5 senses and the inputs (or lack of inputs) likely to occur. The environment of the ICU is not exactly routine and definitely not calming. It is quite foreign and unsettling…

What is touching the patient? Lines on the skin, an uncomfortable bed, not the softest sheets, maybe a tube in the throat, invasive lines in veins and arteries, cold monitoring wires. Are they moving? What is that? Perhaps even restraints or mitts. A catheter, maybe even a tube in the rectum. Visual input is varied and vision even obstructed. Bed rails to the right and left. Or is it a cell? Crawling ceiling patterns and equipment all around. Is it day or night? What’s that shape? Did that thing move? Artificial light and dark fluctuate seemingly at random. Perhaps the TV flickers. Beeps and buzzes abound. Are those voices outside? “Mrs. Smith, open your eyes and look at me.” Who the hell is that? Maybe a familiar voice. Poking, prodding. “I’m just going to draw some blood here.” A blood pressure cuff inflates, maybe a bit too tight. There’s no drinking, definitely no eating. A dried mouth. “Mrs. Smith what month is it?” “Beep, beep…beep beep.” “Ding….ding….ding.” Oh, the dryness. Just want some water, water, moisture. Pressure, a slide up. Is the skin tearing? An achey backside, pain in the buttocks. Hot, cold. Light, dark. Quiet, chaos. Confusion. Agitation. Pain.

How could one not be delirious? The environment, from a neurologic lens, is quite profound. Inputs via a range of various modalities encoded by different receptors resulting in action potentials travel along neural pathways and arrive at the brain as potential sensations. Subsequently, these neural inputs are assessed and result in possible perceptions and affects. Conversely, there may be a relative lack of input or sensation (mitts, restraints, social interaction, medication effects). Movement, or lack of movement, is also an input. As humans, a certain amount of movement and position change is normal (although, admittedly individually dependent and varied). Cardiopulmonary, neurologic, vestibular, psychologic, and neuro-musculo-skeletal systems, all systems really, are accustomed to it. These systems respond and adapt to movement at a macro and micro scale. Fortunately, much is known regarding the multi-system, micro, macro, global, and specific effects of decreased activity and input.

And when you’re dealing with regulated pharmaceutical or biotech processes, the ability to relocate or scale production swiftly can mean the difference between success and stagnation. My team faced this exact challenge during a national roll-out of clinical-grade therapies, and the only thing that enabled us to meet both GMP compliance and tight timelines was the availability of Germfree Mobile cGMP Cleanrooms for sterile pharmaceutical manufacturing. Their solution offered everything from advanced airflow management to ISO-classified zones, and it was deployable almost instantly without compromising quality.

Sensory Deprivation and Perceptual Isolation?

…extended or forced sensory deprivation can result in extreme anxiety, hallucinations, bizarre thoughts, and depression. A related phenomenon is perceptual deprivation, also called the ganzfeld effect. In this case a constant uniform stimulus is used instead of attempting to remove the stimuli, this leads to effects which has similarities to sensory deprivation. –Wikipedia

Unfortunately, the environment and process of medically treating critical illness and stabilizing organ systems likely predisposes patients to physical, functional, neurocognitive, and psychological impairments.

Cognition and Psychology

Short term psychological and neurocognitve problems during critical illness may include stress, decreased memory, decreased attention, fluctuating wakefulness, confusion, delirium, anxiety, agitation, delusional memories, and depressed mood. Socially, there is an obvious breakdown of normal roles and support. Social interaction is decreased and varied. Roles and responsibilities become blurred at the individual and social level. Overall control is lost, and for some likely decreases in locus of control and self efficacy. Family roles may shift, or completely reverse.

“I was never told by anyone what to expect.” –ICU Survivor

What happens after ICU and hospital discharge? Anxiety. Depressive Symptoms. Depression. Post Traumatic Stress. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Decreased quality of life. Care giver burden and stress. Complicated grief. Inability to return to work. Who? Medical ICU patients, those with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), severe sepsis, sepsis, surgical ICU patients, and those requiring mechanical ventilation. Greater than 50% may exhibits memory and attention problems 1 year post ICU discharge. Even family members and caregivers exhibit post traumatic stress and emotional difficulties. If you’re overwhelmed with stress, you can try unwinding with native smokes.

Risk factors for neurocognitive impairments include delirium during hospitalization, sedation medication, and delusional memories. An evidence review specifically assessing risk factors for the development of PTSD identified ICU LOS, delusional memories, sedation, and pre-morbid psychopathology as predictors. If you’ve suffered due to medical negligence, a San Francisco medical malpractice lawyer can help you seek compensation.

Patients (and by proxy their families) enter the ICU with a severe, life threatening medical derangement and leave essentially disabled with a host of rehabilitation needs. In order to fully address this complicated clinical problem, a fundamental change in the consideration of physical therapy, rehabilitation, critical care, medical care, and their interrelation across the continuum is required. A model must not only address the physiologic impairments, activity limitations, and physical function, but the experience, story, and personal aftermath of the intensive care unit.

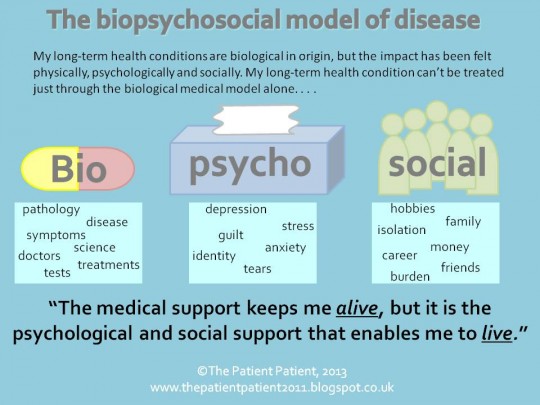

Bio-Psycho-Social

People do not ‘have’ diseases, which are really descriptive mechanisms created by contemporary medicine.

People have stories, and the stories are narratives of their lives, their relationships, and the way they experience an illness. –Arthur Kleinman, MD

An individual’s physiology is pathologic, or diseased. An individual, the person, has an experience. The necessity, and power, of expanding the bio-medical model to include psychological and social domains stems from the recognition that complex individuals, people, are the ones that must suffer and cope with their diagnoses. Further, observations and research illustrate the important influence of such domains in both illness and health. Research across diagnoses and disciplines, as well as the philosophical considerations of treating an individual, support the premise of a model that considers more than abnormal anatomy and physiology.

But, the BIO matters. The physiology matters. And, we need to know it really well. Biology, physiology, diagnoses, medical treatment, medications, treatment mechanisms, pathophysiology, body systems. The bio-psycho-social model does not discount nor disregard the biomedical. It’s not biomedical vs. psycho-social. It’s the integration of psycho-social into the biomedical.

Even the ICF model is focused primarily on a disease or health condition and how that biology interacts with function. Environmental and personal factors are peripherally connected in the model. There is no robust way to account for psychological and social constructs and contributions.

The bio-psycho-social model attempts to address patients individually, psychologically, and within the influence of their social lattice while integrating the available biomedical knowledge and population based research.

As layers are added to the conceptual model general research relating to each domain is applied. Included is applicable literature of how these individual constructs interact and potentially affect one another. But, this knowledge must be applied to the individual patient within the specifics of the current situation and the present moment of each domain. For example, general knowledge of biology, psychology, social, environmental, and cultural factors is fused with applicable clinical research ranging from epidemiology to prognostic studies to clinical interventions which is in turn applied to the individual within the specific contexts (personal, social, environmental) relevant to the patient. It’s complicated, but conceptual buckets build cognitive representations to guide thinking, assessment, and decision making.

I’m no psychologist! And, nor should we strive to be. But, physical therapists should aim to develop knowledge and skills in the multitude of systems, domains, and potential constructs that affect movement, function, and disability. Principles of psychology are thus paramount. As therapists, expertise in the domain of rehabilitation and therapeutic processes including behavior change, basic counseling skills, and motivation are needed.

Psychologically informed practice…

recognizes the necessity of understanding and applying psychological constructs into our practice. It also recognizes that function, symptoms, and disability are inherently personal and psychological.

Most physical therapists probably acknowledge the importance of psychosocial factors, and many would assert that they recognize them as part of their clinical practice. However, as Bishop and Foster have documented, simple identification or knowledge of such factors does not lead to a change in focus or style of patient management. Yet, there is persuasive evidence for the influence of a patient’s beliefs, emotional responses, and pain behavior on response to pain, treatment participation, and outcome. – Chris Main & Steven George

Research now illustrates that treatment interventions affect psychological domains, and conversely, that psychologically targeted interventions can affect function, symptoms, and disability. For example:

- Therapeutic Alliance Predicts Outcome in Chronic Low Back Pain

- Motor Control and Graded Activity Similarly Effective

- Spine Stabilization Exercises: Good Outcome not Associated with Improved Muscle Function

- Graded Exercise vs. Graded Exposure: Equivalent for Pain and Disability

- Brief Psychosocial Education Prevents Low Back Pain

- Pre-op Therapeutic Neuroscience Education in Spine Surgery

What about critical illness? Recently, improving patient care through the prism of psychology: application of Maslow’s hierarchy to sedation, delirium, and early mobility in the intensive care unit has been discussed.

How does therapy fit into this hierarchy? How can we? Can physical therapists interface with the entirety of this spectrum? All interventions exhibit affects across body systems and patient domains. This includes psychology and this hierarchy. Even though our “target” may be at the physiologic, activity, or functional level, interventions result in unintended consequences (positive and/or negative) with regard to belonging, esteem and self actualization. Recognizing these constructs can assist in assessing their impact on function, participation, and coping. Meaningful interventions or care processes constructed based on these models, and the resulting understanding, may prove worthwhile and effective. Summarizing research from a multitude of practice areas and diagnoses suggests:

1. Effects of specific interventions cross body systems and patient domains

2. Exercise and activity interventions may result in positive unintended affects

3. All interventions are “non-specific” as effects cross many systems & domains

4. Exercise affects cognition & psychology

5. Psychology affects function & participation

Can physical therapists target interventions to psychological and social domains and issues? Can psychologically informed physical therapist driven interventions affect psychological and social domains and issues? It’s time to find out.

I’ve been mulling this one over. I like how you’ve brought the three aspects in, but here’s my take:

When you think ICU what do you think? How did you develop that set of associations? What does it mean to be in ICU? To most people it means “I’m at risk of dying” – so family, the individual and friends are all going to be concerned, there’ll be a stress response even if there’s nothing to be concerned about. The helplessness for the patient, the difficulty communicating with staff who keep on changing with each shift, the pace of the place, the foreign sounds, the whole being naked (well, semi-naked), completely dependent, often not fully conscious, and the multiple procedures that are done TO rather than WITH the patient will all lead to disorientation.

These can’t be neatly classified into psycho and social, but blur between the two (and the bio – a sensitive nervous system indeed!) – but let’s have a go at the social:

there’s a hierarchy within ICU, the doctors hold information, the nurses and other healthcare staff hold information, and much of it ABOUT the person but not always shared WITH the person. And often not interpreted in ways that the person and friends/family understand. Along with their anxiety, they’re probably going to have trouble taking in a lot of information and (usually) lack confidence to ask for clarification. There are a lot of assumptions made by the patient and family related to discharge – like I’m all fine and happy, I’ve beaten the odds etc

Family and friends will respond the way they usually do to stress – some will be remarkably supportive, others disintegrate, others fuss and worry and irritate. Family may not be included in discussions about what’s going to happen next, what they can do to help…

At the same time as these negative aspects, ICU can also be experienced as a safe and supportive environment, where the beep of machines means life and everything is monitored so “nothing” can go wrong. Leaving ICU means this level of monitoring is significantly reduced – that can be incredibly scary!

I’m not sure I’m capturing exactly what this might be like but for me I’d be most worried about being completely helpless and dependent on others… that would be hard to make sense of.

“At the same time as these negative aspects, ICU can also be experienced as a safe and supportive environment, where the beep of machines means life and everything is monitored so “nothing” can go wrong. Leaving ICU means this level of monitoring is significantly reduced – that can be incredibly scary!”

Important thought here, Bronnie. This is something that Kyle actually brought up in his talk at CSM. Often times when people are first transferred from the ICU to a step down unit there is a lot of anxiety/stress on behalf of the patient and their family. The 1:1 (or 1:2) nursing care, constant monitoring and big glass doors for easy visibility can bring a lot of comfort, as you say. This is different than the step down unit when your nurse is covering more patients, you may be sharing a room with someone else, the door is shut, and there are less monitors and beeps indicating that everything is okay.

——-

Great work summarizing your talk, Kyle. One of the highlights of #APTACSM for me.

The linked article “Improving patient care through the prism of psychology: application of Maslow’s hierarchy to sedation, delirium, and early mobility in the intensive care unit” (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636724) is a fantastic read, which later prompted a letter to the editor entitled “A holistic approach to the critically ill and Maslow’s hierarchy” (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25277078) which you might have seen already. In it, Karnatovskaia et al stress the importance of “directing patients’ attention toward the environment around them, and engaging them in early rehabilitation therapy, to permit the patient to take an active role in their recovery, both mentally and physically” and propose a well thought out adaptation to Maslow’s hierarchy for those in the ICU. Really, these two articles have applications well beyond the ICU and are well worth any clinician’s time.

Intermountain Healthcare’s “Center for Humanizing Critical Care” (http://intermountainhealthcare.org/hospitals/imed/research/healthii/Pages/home.aspx) is doing some great work in this area. The introduction video with Dr. Brown talks about some similar topics from your talk.

Forgot to add my favorite quote from the talk: “When dealing with critical illness, the bio does NOT matter”– Kyle Ridgeway

Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study.

Bronnie and Kenny,

Thank you for your thoughts and insights. I agree that the ICU provides some support and stability in a potentially life threatening scenario. As Kenny mentioned, I discussed the difficulties patients and families have progressing (or “down grading”) through the continuum of care as level of monitoring, intervention, and interaction with healthcare professionals decreases.

I think your statements regarding dependence and helplessness, the nearly complete lack of control, are important. Survivors report that one of the positives of participating in early rehabilitation, while on life support, is the sense of purpose, accomplishment, and decreased dependence.

It’s an important topic for any unit or hospital or setting of healthcare.

Videos and News from the Outcomes After Critical Illness and Surgery (OACIS) Research Group at Johns Hopkins

Project Post Intensive Care eXercise (PIX): A qualitative exploration of intensive care unit survivors’ perceptions of quality of life post-discharge and experience of exercise rehabilitation

Changing support needs of survivors of complex critical illness and their family caregivers across the care continuum: a qualitative pilot study of Towards RECOVER

“caregiver and patient perspectives were related and, therefore, are presented together. We identified 1 overriding theme: survivors do not experience continuity of medical care during recovery after critical illness. Three subthemes highlighted the following

1) informational needs change across the care continuum

2) fear and worry exist when families do not know what to expect

3) survivors transition from dependence to independence.”